By Sam Intrator, Nancy Zigler, and Yesenia Valentin

Reading the May 2019 Educational Leadership on “What Teens Need from School” got me thinking about an area where teens and young adults especially need support—and aren’t getting it.

Many of us who work in the K-12 world feel a sense of accomplishment when we get a young person launched after high school. Since 2003, Project Coach, an afterschool youth development program I work with, in Springfield, Massachusetts, in which high school students coach and mentor elementary-aged children, has beaten the odds: 100 percent of our participants graduate high school with a plan for college and career. In the K-12 world, this is seen as an indicator of success. But we’ve found it’s not that simple. Consider the words of Yesenia Valentin, who joined Project Coach in 9th grade:

I WAS THE FIRST PERSON IN MY FAMILY TO GRADUATE HIGH SCHOOL WITH A DIPLOMA, THE FIRST TO GO TO COLLEGE FULL-TIME. I REMEMBER WALKING ACROSS THE STAGE AT GRADUATION AND FEELING SO PROUD TO BE BREAKING THE CYCLE. MY FIRST YEAR OF COLLEGE WAS A BREEZE, BUT THEN I HIT A BARRIER . . . DAYS BEFORE SCHOOL STARTED, I WAS NOTIFIED THAT MY FINANCIAL AID FORMS WERE INCORRECT. NEXT CAME A BILL I COULDN’T PAY. I DROPPED OUT AND BEGAN WORKING AT A FACTORY. . . . I FELT STUCK.

Yesenia is a sister, an athlete, a leader in her community. She’s a charismatic coach who makes sports come alive for children. She’s respected by her peers and revered by those she coaches. Among all the things that Yesenia is, the word that comes most to mind is capable. Yesenia didn’t deserve to get stuck.

As we’ve learned at Project Coach, Yesenia’s story—a teen graduates from high school with big dreams and a plan, only to find their momentum derailed by unforeseen challenges—is far too common. The travails of starting college, entering the workforce, and navigating financial responsibilities are formidable. These first steps of adulthood are precarious, and there exists only a patchwork of institutional supports for young adults. The absence of coordinated systems means that youth, particularly from low-income families, face obstacles that upend their progress.

Project Coach began in 2005, when Springfield’s high school four-year graduation rate hovered at about 55 percent and many of the city schools were described as “dropout factories.” One of our goals was to provide an array of supports to help teenagers graduate from high school. Over the years, almost all the youth who’ve participated in Project Coach have graduated, partly because our mentorship model helps youth make meaningful connections to their future, gives them opportunities to practice authentic leadership, and connects them to a Smith College student who provides mentorship.

But as the years passed, we’ve noted a pattern of experiences like Yesenia’s. High school graduation would be a joyous and pivotal moment, plans would be in place to continue the positive momentum, but then program alums would return to visit with shoulders set a little lower.

Alums shared similar stories. With no high school internships and limited work experience, students lacked the financial resources and social capital connections to propel their future. A cosigner for a loan couldn’t be found. A car would stop running. A family wouldn’t know how to help. A future would break down.

In a special report, The New York Times noted that students from lower- and middle-income families often excel in high school only to falter in college. They describe this “college-dropout crisis” as a major contributor to American inequality. A Pell Foundation report found that while 58 percent of young people in the highest family-income quartile achieve a bachelor’s degree by age 24, only 11 percent from the lowest family-income quartile do so. In Springfield, the statistics are even grimmer. Recent U.S. census data shows that only 4.8 percent of Springfield residents earn a bachelor’s degree by 24.

Our Research: Why Young People Feel Stuck

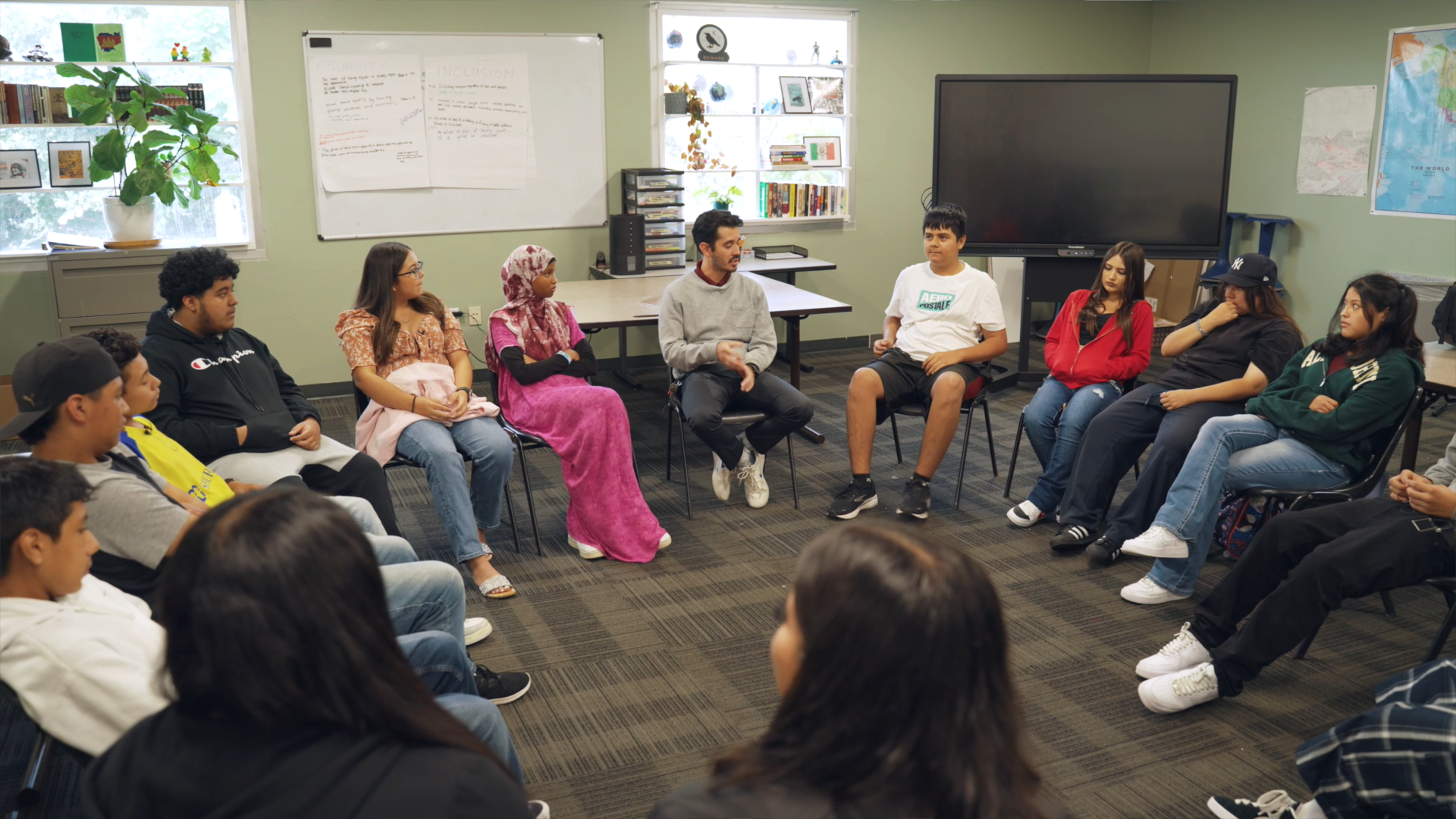

As Project Coach heard more stories like Yesenia’s, we put together a study group to help us understand the conditions that were impacting the pathways of local young people. We assembled a team of people from Smith College and other Springfield organizations. In October 2018, we received a Corporation for National and Community Service grant to launch a participatory action research project–a campus-community collaboration in which youth researchers (18- to 24-year-old Springfield community members) would be co-investigators. Project SPARC—Springfield’s Participatory Action Research Crew–was born.

The first phase of the project was dedicated to co-writing an action plan. To help know what to include in that plan, we interviewed emerging adults in Springfield, asking, What has happened to you after high school?

This question opened up the conversational space as we tried to learn what structures might help students in their messy transition between high school and what happens next. We’ve found that everybody is struggling, no matter how well or poorly they did in high school. We also found this is a conversation not many people are having. Here are the patterns we found.

Life After High School Can Feel Like Freefall

In high school, one interviewee noted, “You’re always being tracked, watched, evaluated, measured,” adding that the structure of high school–daily homework, regular quizzes, ongoing assessments, and overall monitoring by teachers–helps keep students on track. Interviewees said that while they were in high school, they’d viewed this structure as something to be endured. When they got to college, they missed the regimentation and struggled with time management and self-monitoring: “College professors expect you to manage your time, deadlines, and due dates on your own. This was hard for me.”

Youth Yearn for Mentorship During This Transition

Interviewees described how the routine, near-daily connections with adults in high school helped keep them on track. Graduation marked an abrupt end to those supportive encounters. One youth told us, “In high school, I had relationships with teachers, coaches, administrators, security guards, and others. These relationships helped me stay on the path. When you graduate, they go away. It’s lonely.” Other interviewees cited mentorships as contributing to future success, while a lack of such relationships (or toxic relationships) was disproportionately harmful. One youth said he would’ve benefited from having more of a relationship with his guidance counselor: “They help you, direct you, but they don’t even know what you want.”

Bills, Bills, Bills!

We noticed that a common conversation topic among young adults working with SPARC was the problem of their student loans. Interviewees struggled with financial obligations their loans entailed, as well as technical details of their loan agreements.

One interviewee lamented the lack of time spent discussing financial literacy in high school. Another noted, “I wish we had learned about the importance of savings because unexpected big expenses stopped my progress. Others said they wished they’d known about the dangers of loans with high-interest rates. One recent college graduate said she cried each time she went to the financial aid office at her university.

K-12 educators aspire to advance opportunity and help youth move forward in their young adult lives. Yesenia’s story of getting stuck is a powerful reminder to not forget about those who are getting left behind. Our SPARC team is committed to understanding this issue better, forging connections among community members who support youth success, and creating innovative ways to ensure Springfield youth have opportunities to succeed in higher education or careers post-high school graduation. The first year of the grant supporting our project prioritized civic engagement through participatory research; the second year will provide resources to pilot community-designed solutions. We’re devising initiatives that help young adults avoid “getting stuck” by creating, for example, cohorts of recent graduates and mentors who will share knowledge and problem solve together during the first years of young adulthood.

About the authors

Jo Glading DiLorenzo, Jessica Reinert, Joesiah Gonzalez, and the Project SPARC team contributed to this post.